From his perch behind a small cannon aboard the U.S.S. California, Wayne Robinson saw the kamikaze suicide pilot’s plane careening towards the ship.

The 23-year-old gunner had been taking aim as a fellow petty officer fired off rounds at the plane as it descended towards their ship.

“You could see in the cockpit that the pilot was dead. He was hunched over and the airplane was on fire,” he said.

Robinson saw the plane pass by. Although he did not see it hit the ship, he felt the impact.

Amongst the 44 dead were a friend who Robinson had served with since going to gunnery school shortly after enlisting.

“He tried to hide, but he was burnt up,” he said.

In addition to the dead, 144 were injured in the attack that occurred during a battle in the Lingayen Gulf in the Northern Philippines. It was the second bout of heavy combat Robinson and others aboard the U.S.S. California had experienced since arriving in the area a few months earlier.

Although Robinson’s tenure in the military began only months before the kamikaze pilot injured his ship and killed and maimed many aboard, he had been attempting to join the war effort for years.

Robinson first tried to join the Navy in 1941 shortly after Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese. At the time, the 19-year-old was denied entrance because he was working at Union Carbide in Charlestown, W.Va. and his job was considered important to the civil defense war effort.

“I was working in what was considered an important military contractor position, so although I was a civilian I had to request release from my employer,” he said.

It was not until three years later in 1944 that Union Carbide acquiesced to Robinson’s request and he was allowed to join the Navy.

After first being sent to Michigan for basic training, Robinson found himself in Florida for gunnery school before being sent to San Diego to prepare for deployment.For Robinson, the decision to join the military was an easy one. The middle of seven boys, Robinson followed in the footsteps of his three older brothers, who had all served in the military. His three younger brothers would also go into the armed forces as well. Luckily none of the Robinson men were lost in combat

Before shipping out, Robinson was already aware of the dangers of being part of a military operation.

“The U.S.S. California and the U.S.S. Tennessee were following one another back from the Pacific front when they rammed each other. Eight seamen died aboard the California,” he said.

While the ship was being repaired in dry dock, Robinson was put on shore patrol and kept watch over other sailors, a skill that would come in handy later.

After the cruiser was repaired, Robinson finally began the deployment he had been attempting all of those years earlier.

After stopping off in Guam, the U.S.S. California headed to the Philippines where they took part in the Leyte operation. “The Japanese ships knew what we were doing and they tried to bottleneck and surround us,” Robinson said.

During the ensuing skirmish, Robinson served as a gunner pulling the trigger on a set of 50-caliber cannons that could reach targets up to 22 miles away. Although Robinson said it was hard to tell if the cannons made impact, they were able to decimate the Japanese Navy.

“My group had one confirmed ship we sank,” Robinson said.

After the battle, the U.S.S. California faced off against Japanese forces again in the Lingayen Gulf when they were hit by the kamikaze pilot.

Despite the damage to the ship, the U.S.S. California battled on throughout the confrontation. Following the skirmish, the ship headed back to California. Along the way a ceremony was held for those who had died in the battle.

“We buried the sailors who died in the attack at sea,“ Robinson said. “Then put them in bags and put a weight in them before wrapping them in a flag and dropping them overboard.”

The attack took a toll on those aboard and when they returned to port in California many went AWOL.

“We were to go ashore in two shifts, but after half of the first shift didn’t return they didn’t let my shift off the boat,” he said.

With many of the sailors whereabouts unaccounted for, the ship made its way to Hawaii with the intention of going to Alaska.

However, those plans soon changed. The U.S.S. California was heading back to the Pacific Theater as the war was coming to a close and atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The crew finished the war without incident and Robinson even visited mainland Japan after the enemy surrendered.

“We went to Tokyo and the families welcomed us into their homes. There wasn’t any animosity. They were glad that the war was over. We were all glad,” he said.

Following victory in Japan, the U.S.S. California received orders to head to Philadelphia, which presented a navigational struggle for the ship. It was too large to pass through the Panama Canal in Central America and too deep to pass through the Suez Canal in Egypt. So Robinson ended up sailing around the world.

The ship sailed west to India and picked up a number of British troops. Then they went on to South Africa where they dropped off the British troops in Capetown. Finally, the ship crossed the Atlantic and returned to the United States.

After over two years as a petty officer in the Navy, Robinson was released from duty and returned to his job at Union Carbide.

Years later, he and his family would be transferred to St. Charles Parish when the Union Carbide plant, which is now Dow, opened in Taft.

After moving to St. Charles Parish, Robinson engaged himself in community activities. He first joined the Luling Volunteer Fire Department (LVFD) in 1973 and is currently the longest serving member at 41 years of service. For 15 years he served as the LVFD president and oversaw the construction of the current fire station on Paul Maillard Road in Luling.

After 41 and half years at Union Carbide, Robinson retired. However, he wasn’t done working yet. He had become a part-time deputy for the St. Charles Parish Sheriff’s Office years before and held that position for 26 years until finally retiring in 2000 at the age of 78.

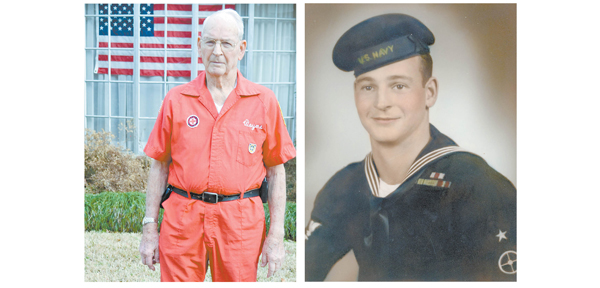

Still, the 92-year-old stays busy and can be often seen wearing a fireman jumpsuit and an emergency radio.

“Every Monday night I still go to training at the fire station,” Robinson said.

This profile is part of an ongoing series between the St. Charles Herald-Guide and the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 3750.

Be the first to comment